Overview of Software Architecture

What is Software Architecture

The concept of software architecture is interpreted across diverse scopes and levels of abstraction, leading to a wide range of definitions. Various definitions have been proposed in academic literature and international standards, including ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010:2011.

Our definition of software architecture is consistent with these established views and aligns with an industrial perspective, as follows:

Software architecture is the design of a system’s structure, architectural views, and architectural tactics aimed at fulfilling both functional and non-functional requirements. It provides a comprehensive and detailed design blueprint that serves as the foundation for system implementation.

This definition highlights three essential aspects of software architecture: (1) structural design, (2) architectural views, and (3) architectural tactics. Structural design refers to the schematic organization of system components and their interactions. Architectural views provide multiple perspectives to address stakeholder concerns and manage system complexity. Architectural tactics are design strategies employed to address specific non-functional requirements.

Why Software Architecture Matters

Software architecture is the most critical design decision in software development. It establishes the fundamental structure of a system, defining its major components, their interactions, and the principles guiding their evolution. The architecture determines how the system will achieve essential quality attributes such as performance, reliability, scalability, and maintainability.

In modern large-scale and AI-enabled systems, architectural decisions directly influence not only technical outcomes but also organizational efficiency and product sustainability. A well-designed architecture enables teams to manage complexity, adapt to changing requirements, and support continuous evolution with minimal rework. Conversely, inadequate architectural design often leads to high maintenance costs, integration difficulties, and poor system performance.

Therefore, software architecture serves as the foundation for both design and implementation. It provides a shared understanding among stakeholders, guides detailed design and development, and ensures that the system’s structure remains consistent with its intended purpose throughout its lifecycle.

Elements of Software Architecture

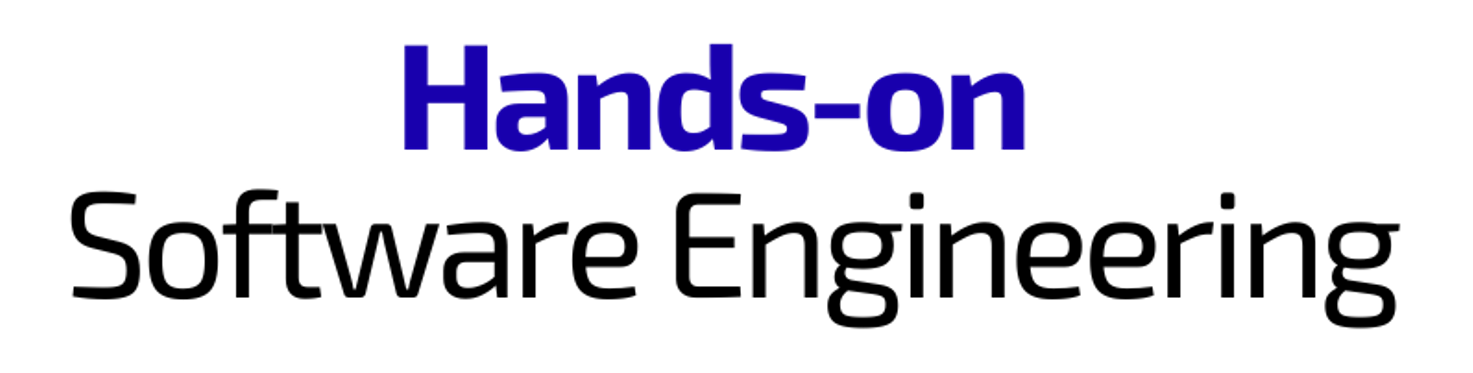

Software architecture is fundamentally composed of three core elements, as shown below.

Reproduced from Hands-on Software Architecture: Unified Architecture Process, Springer, 2025.

Schematic Architecture

Schematic architecture establishes the foundational structure of a software system by defining its major components and their interconnections. It provides a high-level blueprint that captures the system’s organization, including subsystems, layers, and communication paths. This architectural schematic is essential for identifying key design decisions early, clarifying system boundaries, and enabling stakeholders to share a unified understanding of how the system is organized before delving into detailed design.

Design for Architecture Views

Design for architecture views addresses the representation of the system from multiple perspectives, each tailored to specific stakeholder concerns. Typical views—such as context, functional, information, behavior, deployment, development, and operation—highlight distinct aspects of the system’s structure and behavior. This design approach ensures that architectural decisions are communicated effectively across teams, supports analysis of design consistency, and aligns the architecture with both functional and operational expectations.

Design for Non-Functional Requirements

Design for non-functional requirements (NFRs) focuses on embedding system qualities such as performance, scalability, security, reliability, and maintainability into the architecture. Since these qualities cannot be retrofitted later, they must be addressed as integral design concerns from the outset. This element of architecture design identifies architectural tactics and patterns that satisfy NFRs and ensures that trade-offs among competing quality attributes are explicitly managed and validated throughout development.

Software Architects

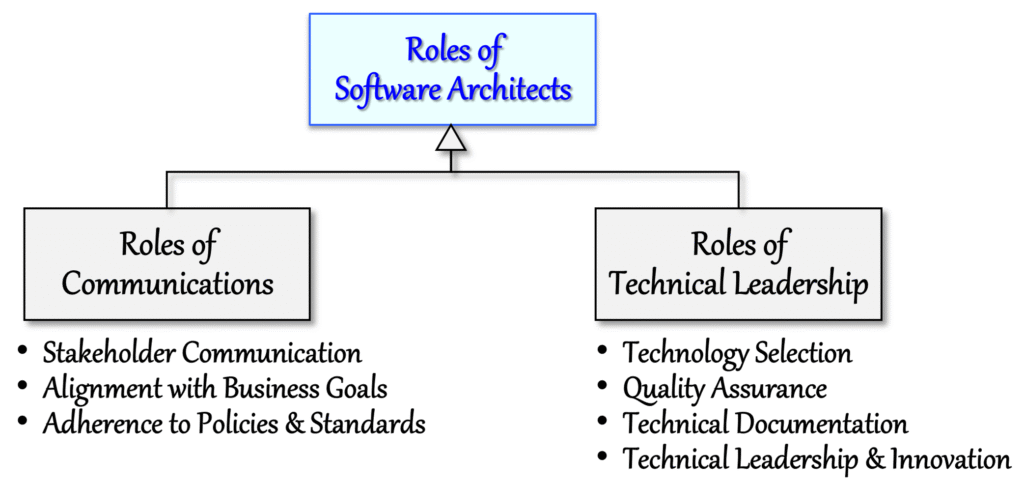

A software architect is a senior-level technical expert responsible for designing a system architecture that defines the overall structure, captures key design decisions across multiple architectural views, and incorporates strategies to meet both functional and non-functional requirements. The roles of software architects can be broadly categorized into two key areas as shown below:

Reproduced from Hands-on Software Architecture: Unified Architecture Process, Springer, 2025.

Roles of Communications

Software architects play a central communication role by connecting diverse stakeholders—business leaders, developers, and clients—throughout the project. They ensure that architectural decisions align with business objectives, clarify technical implications for non-technical audiences, and maintain compliance with organizational policies and standards. Effective communication enables shared understanding, reduces misalignment, and builds trust across all participants in the development process.

Roles of Technical Leadership

As technical leaders, software architects guide technology selection, establish quality assurance practices, and oversee architectural documentation. They drive innovation by exploring emerging technologies while ensuring that design choices remain robust and maintainable. Through their leadership, architects balance strategic vision with technical excellence, fostering a culture of disciplined engineering and continuous improvement across the organization.

Methodology for Software Architecture Design

Designing a robust software architecture poses substantial technical challenges. Without a structured approach, design efforts may result in architectural defects, incomplete or inefficient solutions, poor alignment with requirements, excessive documentation complexity, and increased development costs. A well-defined methodology tailored to architectural design provides an effective way to overcome these issues. The methodological rigor it introduces—ensuring consistency, traceability, and quality assurance—is particularly crucial when developing complex industrial systems with stringent functional and non-functional requirements.

Although software architecture has only recently emerged as a distinct discipline, mature and comprehensive methodologies remain limited. The Unified Architecture Process (UAP) was developed to fill this gap by offering a systematic and scalable methodology for managing architectural complexity and satisfying demanding non-functional requirements. The complete methodology is detailed in the following book:

Soo Dong Kim and Mira Kim, Hands-on Software Architecture: Unified Architecture Process, Springer, Nov. 2025. 517 pp., ISBN 978-3-032-01183-1.

This book is structured into three main parts.

Part I. Overview of Software Architecture

This part introduces the foundational principles of software architecture and presents an overview of the Unified Architecture Process, which serves as the central methodological framework of the book.

Chapter 1. Introduction to Software Architecture

This chapter offers a comprehensive introduction to software architecture, tracing its evolution over time, defining core concepts, and specifying key elements of software architecture. It further explores the challenges associated with architectural design and examines the critical role of software architects.

Chapter 2. Introduction to Unified Architecture Process

This chapter introduces the Unified Architecture Process—a comprehensive methodology for designing software architecture—and outlines guidelines for adapting the process to the specific characteristics and requirements of a target system.

Part II. Guidelines for Unified Architecture Process

This part presents the Unified Architecture Process methodology through detailed guidelines for executing its activities, steps, and tasks. It provides technical rationales, sequential procedures, design templates, examples, and checklists to support deep understanding and effective application. Each chapter in this part corresponds to a specific activity defined in the Unified Architecture Process.

Chapter 3. Activity A1. Requirements Refinement

Chapter 4. Activity A2. System Context Analysis

Chapter 5. Activity A3. Schematic Architecture Design

Chapter 6. Activity A4a. Design for Functional View

Chapter 7. Activity A4b. Design for Information View

Chapter 8. Activity A4c. Design for Behavior View

Chapter 9. Activity A4d. Design for Deployment View

Chapter 10. Activity A5. Design for Non-Functional Requirements

Chapter 11. Activity A6. Architecture Evaluation

Each chapter in Part II includes a comprehensive checklist comprising items that capture the critical design aspects of the activity and reflect established best practices. These checklists serve as validation tools for assessing the outcomes of the activity and ensuring alignment with design objectives.

Each chapter in Part II includes a set of exercise problems intended to reinforce the reader’s understanding of the concepts, principles, design process, and methods presented. These problems are designed to assess comprehension of architectural design principles, promote deeper insight into architectural thinking, and facilitate the practical application of design methods.

Part III. Resources for Software Architecture Design

This part provides two categories of essential and practical resources to support software architecture design.

Chapter 12. Catalog of Architecture Styles

This chapter presents a comprehensive catalog of more than 30 representative software architecture styles. Each style is described with an overview, structural characteristics, collaboration model, and key advantages and disadvantages. Architecture styles serve as foundational building blocks for schematic architectural design.

Chapter 13. Architecture Evaluation Methods

This chapter presents a comprehensive overview of software architecture evaluation methods. Each evaluation method is described with an overview, applicable contexts, procedural steps, and illustrative examples. Architecture evaluation is an essential activity for verifying and validating design decisions prior to system implementation.

Architecture Styles

Architecture Style is a reusable design framework that defines how a software system is organized and how its components interact. It establishes guiding principles and structural constraints for configuring components and coordinating their behavior. Common examples include client–server, layered, model–view–controller (MVC), pipe-and-filter, publish–subscribe, and microservices architectures.

While both architecture styles and design patterns provide reusable design solutions, they differ in scope. Design patterns address specific component interactions at the micro level, whereas architecture styles define the system’s overall structure at the macro level. For example, the Adapter pattern enables communication between incompatible interfaces, while the Client–Server style divides the system into clients that request services and servers that deliver them.

Architecture styles are essential in defining the schematic architecture of a target system. Like design patterns, these styles have been utilized in software engineering for decades, establishing themselves as valuable assets for reusable architecture design.

Classification of Architecture Styles

Architecture styles can be classified by their applicable system types. While there is no universally accepted taxonomy of system types, common types of software systems can be categorized based on their structural and behavioral characteristics. The corresponding architecture styles for each system type are presented as follows.

For Data Flow Systems

A data flow system is characterized by a structural layout composed of multiple components that manipulate and transfer data in a sequential or parallel manner. These components perform specific processing tasks on the data and pass the transformed results to subsequent components

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Batch Sequential Architecture Style

- Pipe-and-Filter Architecture Style

For Data Sharing Systems

A data sharing system is characterized by a structural layout designed to efficiently manage and store large volumes of data accessible by multiple applications. Data is written to and retrieved from a central repository, eliminating the need for direct data exchange between applications.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Shared Repository Architecture Style

- Active Repository Architecture Style

- Blackboard Architecture Style (for Sharing Data)

For Layered Systems

A layered system is characterized by a structural layout organized into a series of hierarchical layers, where each layer provides a well-defined set of functionalities and services to the layer directly above it. The topmost layer typically represents the user interface, while the bottom layer corresponds to the underlying infrastructure.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Layered Architecture Style

- Model-View-Controller (MVC) Architecture Style

- MVC Variations: MVP, MVVM, MVPVM, HMVC, MVA

For Tiered Systems

A tiered system is characterized by a structural layout consisting of multiple tiers, each representing a distinct physical or logical computing environment. Each tier is responsible for a specific high-level functionality and interacts with other tiers to collectively fulfill the system’s overall objectives.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- N-Tier Architecture Style

- Client-Server Architecture Style

- Peer-to-Peer Architecture Style (as a Multi-tier Architecture)

For Load-Balancing Systems

A load-balancing system is characterized by a structural layout comprising multiple servers and a load balancer that distributes computational workloads evenly across the servers. This configuration enhances overall system performance and reliability by preventing server overload and providing redundancy in the event of server failure.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Broker Architecture Style

- Dispatcher Architecture Style

- Master-Slave Architecture Style

- Edge Computing Architecture Style

- Peer-to-Peer Architecture Style (for Load Balancing)

For Event-Based Systems

An event-based system is characterized by a structural layout in which the control flow is driven by the occurrence of events. These events may originate from various sources, including user interactions, hardware devices, software agents, or other system components.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Event-driven Architecture Style

- Publish-Subscribe Architecture Style

- Sensor Controller Actuator Architecture Style

For Service-Based Systems

A service-based system is characterized by a structural layout in which the system leverages external services to fulfill specific aspects of its overall functionality. These external services may include cloud services, microservices, or other distributed service components.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) Style

- Microservice Architecture Style

For Adaptive Systems

An adaptive system is characterized by its ability to modify its behavior and configuration in response to changes in the environment or user needs. Its structural layout comprises both fixed elements, which represent stable, non-adaptable features, and variable elements, which enable dynamic reconfiguration to accommodate evolving conditions.

Applicable architecture styles include:

- Microkernel Architecture Style

- Blackboard Architecture Style (for Sharing Components)

For Other System Types

There can be software systems that do not fit neatly into one category.

Reproduced from Hands-on Software Architecture: Unified Architecture Process, Springer, 2025.